Joy of Christian freedom

It is without doubt one of the most important treatises in the history of the church.

I refer to Martin Luther’s The Freedom of a Christian (1520), sometimes called Christian Liberty. It is a powerful, yet succinct and polemic-free, statement of Luther’s position on how a person is saved and what that entails.

After the Leipzig Disputation of 1519, which we looked at last month, Luther realised that his quarrel with the medieval practice of indulgences was but the tip of the iceberg. His debate with Johann Eck had convinced him that neither the Pope nor general councils were infallible. The basis of authority in the life of the church had to be sola Scriptura, and thus an extensive reformation of the church was a necessity.

Responding to Rome

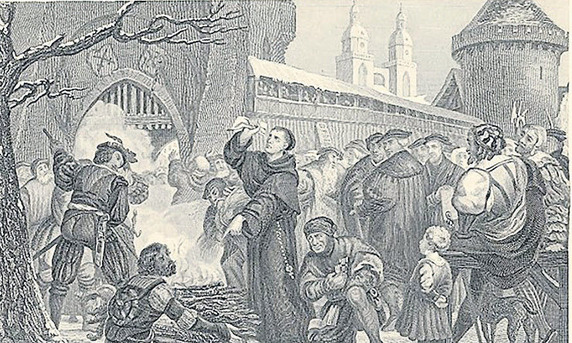

He began to publish at a furious pace his new-found convictions. Between 1517 and 1521 he wrote and published some 30 books, some large, some small treatises like The Freedom of a Christian. This small pearl of theology appeared after Pope Leo X had issued a formal condemnation of Luther’s teachings in the papal bull (bulla) known as Exsurge Domine that began with a call to God to rise up and rid his vineyard of a wild German boar, that is, Luther!

Exsurge Domine was issued in mid-June 1520. Within six months the German Reformer had penned three major tracts. First, there was To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (August 1520), which called upon the German aristocracy to take in hand the reform of the Church since it was increasingly apparent to Luther that the Pope and his advisers in the Roman Curia were not going to do so. The Babylonian Captivity of the Church (October 1520), a massive examination of medieval Roman Catholic sacramental theology, came out two months later. Both of these two works are large treatises and Luther must have been writing and researching virtually non-stop!

What is Christian liberty?

The much smaller tract The Freedom of a Christian then appeared in November in both Latin and German. It is really Luther’s confession of belief that he rightly believed was both the Ancient Faith and a pure distillation of the biblical perspective on the basis of true Christianity.

Luther begins with a paradox: ‘A Christian is an utterly free man, lord of all, subject to none. A Christian is an utterly dutiful man, servant of all, subject to all.’

How can a person be at once both free and enslaved? Well, he or she is free since by faith in the crucified and risen Lord they are declared to be right with God. They do not need to live in a so-called holy place like a monastery or nunnery to know God fully and they do not need to have take special vows of dedication to God as a monk or nun or priest. They simply need to believe on the Lord Jesus.

Likened to marriage

Luther famously compares faith in Christ to the ring used in marriage. Just as the ring symbolizes the marital union of a man and a woman in which all that belongs to the one is now the property of the other, so it is with faith. Faith declares that the sinner has been brought into a living union with Christ in which the Lord Jesus takes all that the sinner has, which is but sin, as his own. He is counted a sinner and bears those sins in his body on the cross.

But equally all that Christ possesses as a human being, namely, his perfect righteousness that he achieved through the entire fulfillment of the law, belongs by imputation to the believer. So faith alone justifies.

What about good works?

Are good works then not needed and is the Christian free to live as he or she pleases? Not so, Luther says, for good works are to faith as fruit is to a fruit tree. Where there is true faith there will be good works that flow out of this faith. In other words, as Luther’s spiritual descendant Jonathan Edwards once put it, no one is saved by works, but no one is saved without works.

The believer does not need the works to be saved, but those who are the beneficiaries of the works need them to live in this world. In fact, since works are not needed for salvation, the believer can truly love his neighbour with them. In the medieval system, good works are needed to wing one’s way through purgatory, and the recipient of the works, the Christian’s neighbour, then becomes a means to an end: the believer’s salvation. But in Luther’s vision of the Christian life, since the believer does not need good works for salvation, he or she can truly love and serve his neighbour through them. Little wonder then Luther could speak of ‘the glory … and joy of Christian freedom’.

Michael Haykin is Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville, Kentucky.