The difference between an evangelical and a non-evangelical understanding of holiness can be seen well in a difference between the 17th-century Puritans and their contemporaries, the high-church Caroline Divines. Perhaps the most influential of the Carolines was William Laud (1573–1645), Charles I’s Archbishop of Canterbury.

Laud loved what he called “the beauty of holiness”, by which he meant liturgical orderliness. He strictly insisted that the clergy must follow all the rubrics of the Church of England’s prayer book, and was deeply concerned with clergy attire and the maintenance of church buildings and their physical beauty. And it was a particular sort of building he preferred: despising the Reformation – or “Deformation,” as he called it – he preferred new churches to be built in the pre-Reformation, Gothic style, with an architectural emphasis on an altar instead of a Communion table. For, he said, “the altar is the greatest place of God’s residence upon earth, greater than the pulpit; for there ’tis Hoc est corpus meum, This is my body; but in the other it is at most but Hoc est verbum meum, This is my word.”

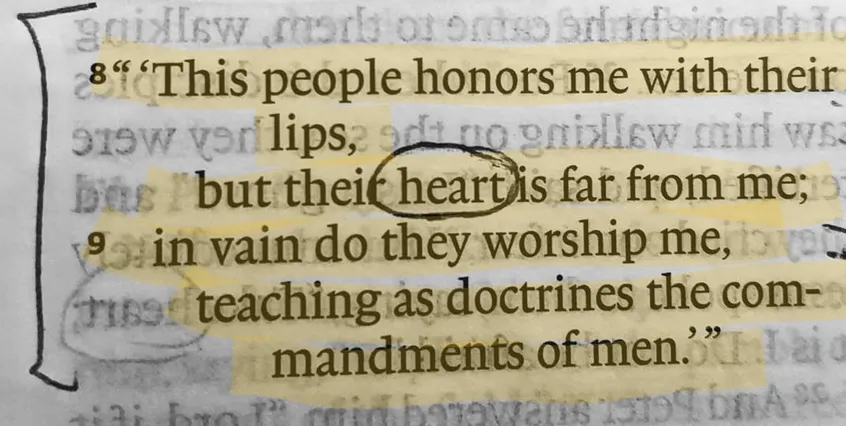

All of this was most revealing of his theology. William Laud’s preference for altars over pulpits always tended toward an emphasis on the necessity of ongoing priestly mediation by the clergy, as opposed to an emphasis on the completed work of Christ. But also, that emphasis on ceremony, architecture, and correct liturgical procedure reflected the Caroline idea that we change from the outside-in. The stress, then, would not be placed on the need for personal faith, but on the need for external things to be done rightly. Right dress, right act, and right behaviour were the prime concern.

Can 'celebrity Christianity' disciple you effectively?

We live in a golden age of Christian content, but at the same time it is a fragile age for …