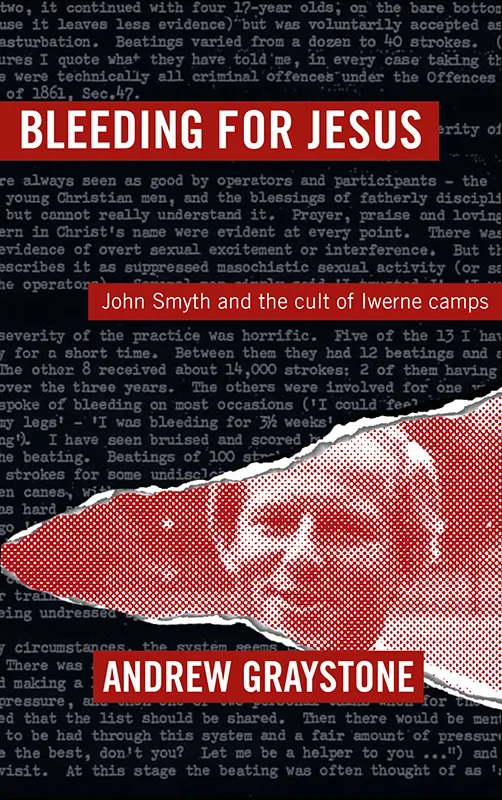

BLEEDING FOR JESUS:

John Smyth and the cult of Iwerne camps

By Andrew Graystone

Darton, Longman and Todd, 240 pages £12.99 paperback

ISBN 978 1 913 657 123

What became known as ‘Iwerne camps’ began 90 years ago, bringing profound benefit to the church. They were founded by a man called Eric Nash, nicknamed Bash, and were often known as ‘Bash camps’ or simply as ‘Iwerne’, after Iwerne Minster in Dorset, where they were held.

Former Iwerne campers include senior leaders in the military, in business and in education, and well-known church leaders like John Stott, Dick Lucas, Nicky Gumbel, Michael Green and Justin Welby. They also include lesser-known names of men who have invested their lives in serving urban housing estates, or in world mission. All the boys were drawn from the UK’s elite schools. Iwerne was no cult. Andrew Graystone’s book presents Iwerne camps as synonymous with the exercise of abusive power, rather than with the spirit of service.