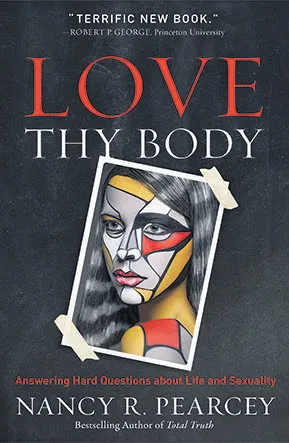

LOVE THY BODY:

Answering Hard Questions about Life and

Sexuality

By Nancy R. Pearcey

Baker Books. 335 pages. £14.99

ISBN 978 0 801 075 728

There was a time when Christians occupied the high moral ground.

People may not have lived by Christian moral standards, but many at least gave lip service to them. No more. ‘Why can’t I be who I want to be and love who I want to love and have a baby only if I want a baby, and die when I want to die. Who is it hurting? Why should some intolerant religious nut tell me what to do?’ We are losing the argument, losing the culture wars and losing the younger generation. The question in too many young minds is no longer whether Christianity is true, but why Christians are such bigots.