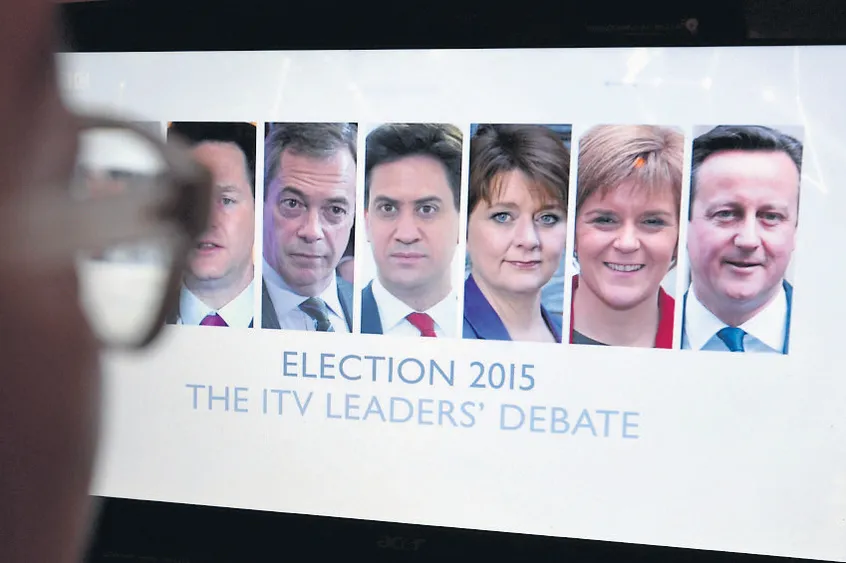

George Moody reflects on the outcome of May’s General Election

The voters have spoken. Yes, the Conservatives are back, but it is in no small part due to the rise of nationalism.

So what is nationalism? It can be defined in different ways. In one way, the emphasis is on the feeling of affection or identity with your own country. Such a sense of loyalty or pride at being a member of a particular nation is often highly visible during sporting events. For those of us lucky enough to be present at the London 2012 Olympics, it is hard to forget the pleasure of being part of a great national moment. We had put on this great show, even if we had actually done nothing more than buy a ticket. It warmed the heart of a nation.